The President who led transition to democracy dies. His moral standing survives.

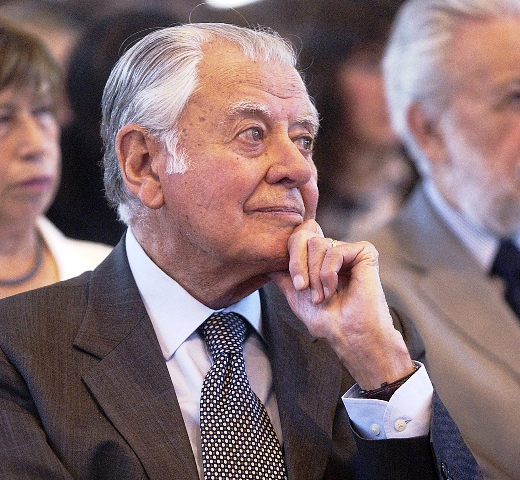

Former President, Patricio Aylwin Azocar, dies at age 97. For three days, Chileans have mourned their first democratically-elected president - after Pinochet's demise. Aylwin is remembered as the just, fair man who led the transition to democracy and made of reconciliation in Chile the basis for a smooth shift to democracy, proving his hard-line detractors that democratic life was possible and attainable without military intervention. His political doctrine was "progress within the realm of the possible". There were countless gatherings of citizens showing genuine affection and heartfelt comments on his contribution to democracy. From former cabinet members to key political figures at the time were present, but also figures from the opposition. Alongside the media coverage of his farewell, both nationally and internationally, his departure has opened the much-needed space for reflection on the 25-year political cycle since Pinochet was electorally forced to step down. The mood of reflection amongst the political elite and across the nation itself is calling the times to adjust the engine of governmental affairs onto the firmness of moral grounds that characterized Aylwin's presidency and most importantly, his political decisions in the face of tough times to secure a strong democracy in Chile.

Aylwin - the right man for the times

In one of his late interviews, Aylwin confided that Pinochet hoped for the "political class" to make grave mistakes that would make the population disenchanted so they might call for the military to return to power. Aylwin knew all along, but he did no waver. Despite his apparent fragility - he was a 71-year-old man - and notwithstanding his anti-hero appearance but his insightful mind, he actually managed to deceive Pinochet himself, using his calm and quiet countenance. Because in the face of the many threats that the military made when Aylwin was going too far in his quest to know the whereabouts of the "disappeared" in dictatorship or when Aylwin even allowed for a free, independent press in the Government's TV Channel - one that began to enjoy autonomy to publish, and do investigative reports - Aylwin always managed to calm down the turbulent waters and appease the General.

Indeed, it was extraordinary for many that when Aylwin rose to the Presidency of Chile in 1990, Pinochet was still retaining his role as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces Despite a clear "No" from the population in the 1989 referendum on the possibility of a prolonged period of military rule, the democratic elections that took Aylwin to power as the first elected president after Pinochet's dictatorship, meant only one path to civil rule: the understanding that Chilean transition could only go ahead on condition that the spheres of power around the military were kept intact. And thus, Pinochet remained as Commander in Chief and then the General became a member of Senate for life as it had been agreed.....until his arrest in London in 1998.

Tough times did now wait to show up

Indeed, his presidency was not free from those turbulent waters, but he sailed always confident that his moral fabric would advise him well. When many were worried a pursuit to find the truth about the tortured, the disappeared, the dead during Pinochet's rule would put the fragile democracy on perilous grounds, Aylwin remained firm in his conviction that an early democracy was much more than keeping the economic model afloat, much more indeed that trying to show convivial interactions with Pinochet and his military, and fundamentallly a lot more than macroeconomic balance. He knew the fabric of reconciliation was of moral nature, and in order for Chileans to converge in harmony and reconciliation, men and women, military and civilians, all, should know what had actually occurred in the dictatorship.

To that end, he summoned the Truth and Reconciliation panel, led by Rettig in 1990. After 9 months of exhaustive investigation, the Reconciliation panel brought about a dossier of 4 volumes detailing 2.115 victims of human right violations, 2.279 who lost their lives, and 165 who were politically persecuted. This dossier was submitted to Aylwin in February 1991. On hearing the news, Pinochet prepared himself and his black berets men on alert. Aylwin - instead - addressed the population on TV, then he asked for forgiveness on the name of the Chilean state to all victims of human rights violations, with a broken voice, he said he was sorry for the atrocities committed to Chileans.

By 1993, one last time, perilous times came. When the national newspaper "La Nacion" announced that the "pinocheques" corruption case - involving Pinochet's son and the military in a fraud scheme - would be re-opened, Pinochet mobilized his black berets men and tensions grew high. By then, Aylwin was in Europe on a presidential visit; despite the tensions and military movements, he did not change his itinerary and waited for turbulence to appease asking his ministers to remain calm and be very, very patient.

The politics of "consensus"

Aylwin was clear that a new kind of politics was needed. He knew reconciliation meant the political reunion of all forces in Chile and took a leading role in that regard. He brought to the negotiating table the combatant left wing activists and leaders of the unions (like Mr Bustos) face to face with the right wing entrepreneurial elite to find accords, to negotiate new terms of agreements between capital owners and workers on important issues such as the first tax reform that shifted the neoliberal economy to market society. It was the beginning of the consensus politics. Not the realpolitik, but a politics ruled by pragmatism, with strict adherence to the law - Aylwin was a lawyer himself.

He stamped his hallmark in that consensus politics. To serve the state, not to be served by the state. His austerity, almost humble manners, were patent when USA's George Bush visited Chile. Not the Presidential Palace, but his home. Surrounded by Aylwin's family and children.

His legacy

Aylwin's legacy should make us all reflect. As the "fair man, the good man" he was - in words of President Bachelet at his funeral - his legacy is compelling to follow his example. Aylwin was a member of the Falange, the Chilean Christian Democracy (DC- Partido Demócrata Cristiano) political party. At his funeral, it was Christian Democracy's current president - Carolina Goic - who asked for forgiveness following Aylwin's legacy on a moral compass, due to the weakness of politicians involved in the recent cases of attrition and corruption in the wake of the 25-year political cycle.

Goic stated she was sorry when authorities appear to have misunderstood that getting to power meant to serve particular interests or even personal goals, and seemed to have forgotten they had been only elected to serve the country and not be served by the country. Those words echo in the media and reverberate today in the national soul. On his departure, Aylwin is telling us democracy is always fragile and those who guard against its many menaces are those whose countenance is humble and austere; those whose main ambition feeds on commitment to the common good, who take calm decision but do not waiver on moral conviction and make progress "within the realm of the possible".

April 23rd, 2016 - Soledad Soza